Recursive Decomposition

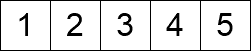

In this course, we focus on the idea of algorithmic decomposition—solving a problem by solving relevant sub-problems. We realize the solution to these sub-problems primarily through definitions and functions. For example, consider a familiar image from a previous reading:

(import image)

(define tree

(above

(triangle 50 "solid" "green")

(rectangle 10 50 "solid" "brown")))

(define cottage

(above

(triangle 100 "solid" "blue")

(rectangle 80 75 "solid" "brown")))

(beside/align "bottom"

tree

tree

cottage

tree

tree)

We broke up this cottage into smaller sub-images, e.g.:

- Trees.

- The cottage itself.

We then wrote definitions for the trees and cottage and them composed them together (via beside/align) in this case) to form the final picture.

However, what about this image?

(import image) (overlay (triangle 250 "outline" "blue") (triangle 225 "outline" "blue") (triangle 200 "outline" "blue") (triangle 175 "outline" "blue") (triangle 150 "outline" "blue") (triangle 125 "outline" "blue") (triangle 100 "outline" "blue") (triangle 75 "outline" "blue") (triangle 50 "outline" "blue") (triangle 25 "outline" "blue"))

Oof, that code is pretty redundant! How can we decompose this image to remove that undesirable redundancy?

Last week, we learned how we might recast the problem as a list transformation problem:

- Start with a triangle’s “index” in the image.

- Transform the index into a triangle length.

- Turn the length into a triangle.

- Combine the triangles with overlay.

We can then use mapping transformations over lists to perform this operation uniformly over all triangles.

(import image)

(|> (range 10)

(lambda (l) (map (lambda (i) (* 25 (+ i 1))) l))

(lambda (l) (map (lambda (n) (triangle n "outline" "blue")) l))

(lambda (l) (apply overlay l)))

This works. However, let’s consider an alternative decomposition that better captures the “heart” of this image.

(import image) (overlay (triangle 250 "outline" "blue") (triangle 225 "solid" "blue"))

Here, we can decompose the problem into two sub-problems:

- Creating the outermost triangle (the outline)

- Creating the rest of the triangles (the solid triangle).

And then we can combine the results with overlay.

We know how to create the outermost triangle with a call to triangle.

But what about the rest of the triangles?

The answer to this question is the insight that we’ll study for the next part of this course:

The problem of creating the rest of the triangles is the original problem, just smaller. It is smaller by exactly one triangle.

This idea that we can decompose a problem into a smaller version of itself is called recursion. Recursion is a cornerstone of algorithmic design in computer science. Many problems are expressed beautifully and concisely using recursion. However, recognizing that a problem can be decomposed using recursion requires substantial practice, so we will take our time working through and understanding this approach to problem solving.

Decomposing Lists Recursively

We’ll begin our study of recursion by revisiting the list datatype and explore how we can work with lists recursively.

For example, here is a picture that represents the list (list 1 2 3 4 5).

A recursive interpretation of a data structure involves being able to express that data structure in terms of a smaller version of itself. In other words, where in this overall list do we see a small list lurking? The interpretation that we use in functional languages like Scheme is the following:

Here, we identify the head element of the list, 1.

By doing this, we can see that the rest of the list, its tail, is simply the remainder of the elements—they form a smaller list!

We can then look at the remainder of the list under the same lens: the head element of this smaller list is 2 and the tail of that sublist is yet another list.

This continues until we reach the end of the list.

We say that the tail of the sublist whose head is 5 is the empty list, or null.

Taking a step back, we can use this perspective on lists to give a definition of a list in terms of its possible shapes.

A list is either:

- The empty list.

- A non-empty list consisting of a head element and a sub-list, its tail.

Because the non-empty list case contains a list, we say that the this definition is recursive, i.e., it references itself.

In Racket, the car and cdr functions (pronounced “car” and “could-er”, respectively) allow us to decompose a list in this manner, respectively:

(car (list 1 2 3 4 5)) (cdr (list 1 2 3 4 5))

Note that these functions only “make sense” when the list in question is non-empty.

If we try calling these functions with the empty list, null, we receive errors:

(car null) (cdr null)

Note that these errors say that pair is expected instead of a list.

There’s a specific reason why the error says this, but for now, just note that if you call car and cdr on empty lists, you’ll receive these errors.

To ensure that we don’t call car and cdr on an empty list, we can use the null? function which takes a list as input and returns #t if and only if the list is empty, i.e., null.

As an example, here is a use of car, cdr, and null? in combination to define a function singleton? that returns #t if the input list contains exactly one element.

(define singleton?

(lambda (lst)

(if (null? lst)

#f

(null? (cdr lst)))))

(test-case "singleton example"

equal?

#t (singleton? (list 5)))

(test-case "non-singleton example"

equal?

#f (singleton? (list 3 1 5 2)))

(test-case "empty list example"

equal?

#f (singleton? null))

We can read the definition of singleton? as follows:

- If the list is empty, then it is not a singleton.

- Otherwise, the list is a singleton if the tail of the list is empty. We know this because in the else-branch of the conditional, we know the list contains at least one element, its head. So it is sufficient to check to see if the tail is empty which would imply there are no more elements other than the first.

Those who have embraced the Zen of Boolean might express singleton? as:

(define singleton?

(lambda (lst)

(and (not (null? lst))

(null? (cdr lst)))))

(test-case "singleton example"

equal?

#t (singleton? (list 5)))

(test-case "non-singleton example"

equal?

#f (singleton? (list 3 1 5 2)))

(test-case "empty list example"

equal?

#f (singleton? null))

Both versions align with our recursive definition of a list:

A list is either:

- Empty or

- Non-empty with a head element and the rest of the list, called its tail.

car, cdr, and null? allow us to use with lists using this particular decomposition in mind.

We can build lists using this head-tail distinction with the cons function.

(cons x xs) creates a new list by appending the element x to the front of the list xs.

(cons 1 (list 2 3 4 5))

Because the second argument to cons is a smaller list, we can use cons repeatedly to obtain the same effect as our list literal syntax:

(test-case "list and cons produce the same results"

equal?

(list 1 2 3 4 5)

(cons 1

(cons 2

(cons 3

(cons 4

(cons 5 null))))))

Note that null itself is a list, but since it is empty, it effectively ends this chain of calls to cons.

A First Example: Summation

With our new list functions, let’s define a procedure called sum that takes one argument, a list of numbers, and returns the result of adding all of the elements of the list together.

You already know one way to compute sum: You just fold the list with the + function.

Recall that (fold f init l) is identical to (reduce f l) except that we start with initial value init in our “summary” computation rather than the first element of l.

(define sum

(lambda (numbers)

(fold + 0 numbers)))

(sum (list 91 85 96 82 89))

(sum (list -17 17 12 -4))

(sum (list 9.3))

(sum null)

But let’s try to implement sum not with reduce but recursive decomposition instead!

How can we decompose the problem of implementing sum using our recursive definition of a list?

We first recognize that null? allows us to easily express the two cases we outlined in the definition:

null?is#t: how do wesuman empty list?null?is#f: how do wesuma non-empty list?

This leads us to the following initial skeleton for sum:

(define sum

(lambda (numbers)

(if (null? numbers)

; The sum of an empty list

; The sum of a non-empty list

)))

The sum of the empty list is easy—since there’s nothing to add, so the total is 0.

However, what about the non-empty list case?

Well, we know that since the list is non-empty that car and cdr work on the list.

Let’s revisit the concrete list from before: a list containing 1 at the head with an unknown set of elements as its tail:

If this list is numbers then (car numbers) produces 1 and (cdr numbers) produces the tail of the list (filled in to represent the fact that we don’t immediately know its contents).

How can we decompose the sum of numbers in terms of these components?

If we had a way to sum up the tail of the list, we could simply add the head of the list to the result.

In code, this is expressed as:

(+ (car numbers) {??})

Where {??} is the hole we need to fill in with “sum the tail.”

The tail is expressed with (cdr numbers); we just need a function to that sums up the elements of a list for us.

Luckily, that is exactly the function we are defining right now:

(+ (car numbers) (sum (cdr numbers)))

Here, the sum function is being called in its own definition.

This is called a recursive function call.

If we believe that such a function call works, then we see that our decomposition is valid:

The sum of the elements of a list is the head of list added to the sum of the tail.

Here is the complete recursive definition of sum.

Observe how the definition of sum mirrors our decomposition:

Numbers is either an empty list or a non-empty list.

- The sum of an empty list is

0.- The sum of a non-empty list is the head of the list added to the sum of the tail.

(define sum

(lambda (numbers)

(if (null? numbers)

0

(+ (car numbers) (sum (cdr numbers))))))

(sum (list 91 85 96 82 89))

(sum (list -17 17 12 -4))

(sum (list 9.3))

(sum null)

Recursion and our mental model of computation

At first, this may look strange or magical, like a circular definition: if Scheme has to know the meaning of sum before it can process the definition of sum, how does it ever get started?

Our mental model can show us how this function computes!

Let’s consider a simple example: (sum (list 5 8 2)).

(We’ll skip a few intermediate steps along the way to highlight the relevant parts of the derivation.)

-

The argument to

sumis a value, so we go ahead and substitute for the body of the function:(sum (list 5 8 2)) --> (if (null? (list 5 8 2)) 0 (+ (car (list 5 8 2)) (sum (cdr (list 5 8 2))))) -

The list

(list 5 8 2)is non-empty, sonullevaluates to#f. This means the conditional evaluates to its else-branch:(if (null? (list 5 8 2)) 0 (+ (car (list 5 8 2)) (sum (cdr (list 5 8 2))))) --> (if #f 0 (+ (car (list 5 8 2)) (sum (cdr (list 5 8 2))))) --> (+ (car (list 5 8 2)) (sum (cdr (list 5 8 2))))) -

(car (list 5 8 2))evaluates to5and(cdr (list 5 8 2))evaluates to(list 8 2). This leads to the following simplified expression:(+ (car (list 5 8 2)) (sum (cdr (list 5 8 2))))) --> (+ 5 (sum (cdr (list 5 8 2))))) --> (+ 5 (sum (list 8 2))) -

Now, we substitute for the body of

sumagain but this time passing the argument(list 8 2):(+ 5 (sum (list 8 2))) --> (+ 5 (if (null? (list 8 2)) 0 (+ (car (list 8 2)) (sum (cdr (list 8 2)))))) -

Note that the

(+ 5 ...)from the original call tosumis waiting to be evaluated, but we must first deal with this new conditional! Also note that we’re in a similar situation as step 2 except that the list in question is(list 8 2)instead of(list 5 8 2). To proceed, we note that(list 8 2)is non-null, so we evaluate to the else branch. Evaluating(car (list 8 2))yields8and(cdr (list 8 2))yields(list 2), the list containing just2. This gives us the following derivation:(+ 5 (if (null? (list 8 2)) 0 (+ (car (list 8 2)) (sum (cdr (list 8 2)))))) --> (+ 5 (if #f 0 (+ (car (list 8 2)) (sum (cdr (list 8 2)))))) --> (+ 5 (+ car (list 8 2)) (sum (cdr (list 8 2)))) --> (+ 5 (+ 8 (sum (cdr (list 8 2))))) --> (+ 5 (+ 8 (sum (list 2)))) -

At this point, you can see a pattern—we’ll peel off each element from the list going from left-to-right. That element becomes part of the overall sum. As an check, you will work through the derivation from the expression above to this state:

(+ 5 (+ 8 (sum (list 2)))) --> ... --> (+ 5 (+ 8 (+ 2 (sum null))))But what happens now when

sumis passed the empty list? Let’s substitute one more time and find out:(+ 5 (+ 8 (sum '()))) --> ... --> (+ 5 (+ 8 (+ 2 (if (null? null)) 0 (+ (car null) (sum (cdr null)))))) -

Finally, the input list is the empty list, so our conditional goes into the if-branch:

(+ 5 (+ 8 (+ 2 (if (null? null) 0 (+ (car null) (sum (cdr null))))))) (+ 5 (+ 8 (+ 2 (if #t 0 (+ (car null) (sum (cdr null))))))) --> (+ 5 (+ 8 (+ 2 0)))You may have been worried that

(car null)and(cdr null)are invalid expressions. However, recall thatifdoes not behave like a function call. We only evaluate the branch containing the offending code when the guard of the conditional is#f! In this case, the guard evaluated to#t, and so we never got to the invalid expressions. -

We see that the final call to

sumyields 0. From here, we finally compute the sum, giving us the final result:(+ 5 (+ 8 (+ 2 0))) --> (+ 5 (+ 8 2)) --> (+ 5 10) --> 15

Self checks

Check 1: Complete the missing part (‡)

Fill in the missing steps of the derivation from step 6 above:

(+ 5 (+ 8 (sum (list 2))))

--> ...

--> (+ 5 (+ 8 (+ 2 (sum '()))))

Check 2: To infinity and beyond (‡)

Consider the following erroneous definition of sum:

(define awesum

(lambda (lst)

(if (null? lst)

0

(+ (car lst) (awesum lst)))))

The only difference between awesum and sum is that we passed lst rather than (cdr lst) to the recursive call.

What happens if we call (awesum (list 5 2))?

Use your mental model to predict the result, and then check your result in Scamper.

Explain your findings in a few sentences.

(Warning: make sure you save your work before checking!)